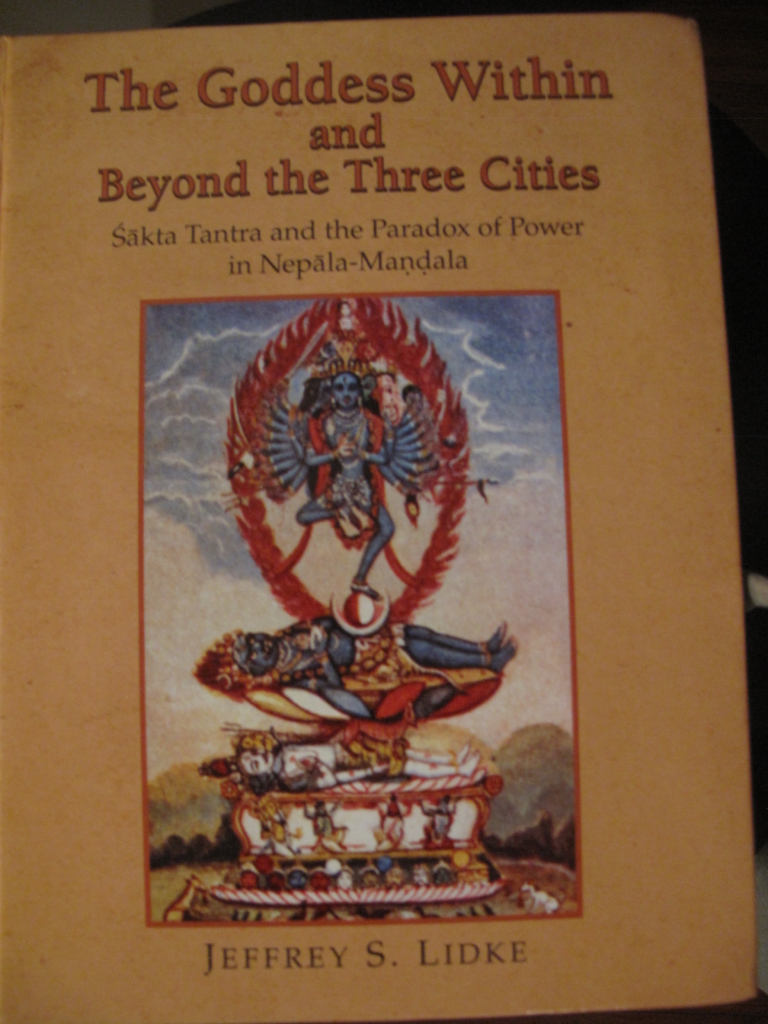

The Goddess Within and Beyond the Three Cities: Sakta Tantra and the Paradox of Power in Nepala-Mandala by Jeffrey S. Lidke. DR Printworld: New Delhi, 2017; Re.2200; USD 57.00(Hardcover); 376p.; 29 color and b/w photos; appendices, glossary, bibliography; index. ISBN 978-81-246-0876-0

The Goddess Within and Beyond the Three Cities: Sakta Tantra and the Paradox of Power in Nepala-Mandala by Jeffrey S. Lidke. DR Printworld: New Delhi, 2017; Re.2200; USD 57.00(Hardcover); 376p.; 29 color and b/w photos; appendices, glossary, bibliography; index. ISBN 978-81-246-0876-0

As someone with roots in Nepal, I am drawn to books and articles that deal with my home country. Though my plate was full when I was approached to review Jeffrey Lidke’s book, The Goddess Within and Beyond The Three Cities, I simply could not pass up the opportunity. After reading it, I’m happy to confirm that I’m glad to have accepted the challenge; it was well worth the time and effort.

This book is the result of the author’s many years of interest in Nepali art, culture, and religion. I knew Jeffrey Lidke when he was a young graduate student at the University of California in Santa Barbara. At the time I met him, he was preparing to go to Nepal with a Fulbright; I remember writing a letter in support of his Nepali language proficiency. Now that Lidke has successfully earned his Ph.D. degree and is gainfully employed at a college, teaching courses in South Asian religions, I am more than happy to review his book. With many journal articles, book chapters, and, finally, a book of his own, Professor Lidke has emerged as a young leading scholar in the small field of Tantric studies.

Since the beginning of known history, Nepal has been a seat of Tantrism. Lidke naturally has focused his attention on the goddess tradition, which delivers power to the practitioner. The concept of Shakti, which the Hindu goddess embodies, is about power. In the realm of politics, it is Shakti through which the leader derives his or her power; it is the quintessential element without which the leader cannot govern, whether it is a country or a corporation.

It will become apparent why the goddess Taleju Bhavani was designated as a tutelary deity of the ruling house of Nepal. Brought to Nepal in 1324 CE by King Hari Simha Deva of Simrongarh, the goddess makes her entry in the Kathmandu Valley, never to leave the country. She has been firmly rooted in the Valley since the early part of the 14th century, serving as the tutelary deity of the kings and rulers of Nepal. Every Nepali ritual and festival revolving around the goddess must be understood in the context of goddess and her role as a giver of Shakti (power) to the worshipper. The mandate to govern is granted by Taleju, and it is the most important aspect of the Nepali Tantric religion. Just as the goddess and her Shakti cannot be separated from each other, neither can the ruler and his or her power. Shakti is an essential part of a ruler.

The Goddess Within and Beyond The Three Cities is an excellent study of Nepal’s Tantrism, in which Lidke sifts through many years of research data to arrive at the conclusion that Shakti manifests everywhere. The book makes copious references to Sthaneshwar Timalsina and the many conversations Lidke had with him during his stay in Kathmandu. Additionally, the book contains a forward by Timalsina himself, in which he provides a well-articulated context for Lidke’s body of work.

I am amazed at the volume of textual references cited in the book, making it a truly scholarly masterpiece. Inspired by Sri Vidya, a specific Tantric deity also known as Tripurasundari of the dasa mahavidya family, Lidke focuses his study through the Nityasodasikarnava, as practiced by the Nepali Tantrikas of the Kathmandu Valley. Lidke’s book is divided into four main chapters:

- The Goddess Embodied: Tripurasundari and the Tricosmos

- Tantric Sadhana: Harnessing the Power of Shakti

- The Mandala Hologram: Centers, Peripheries and the Dance of Power

- The Reverberating Goddess: The Kumari and the King

In Introduction: Tracking the Stories of Devi, Lidke sets the stage for the appearance of goddess in the Kathmandu Valley, tracing her origin to India. Lidke says, “Textual, epigraphic, and oral sources indicate that from the eighth century on, Nepalese kings from each of the three major dynastic lineages—Lichchhavi (c. fourth to ninth century), Malla (1200-1769), and Shah (1769-present)[1] —have appropriated a variety of Tantric ideologies and practices that were brought to Nepal from India, including not only Kula and Yogini traditions but also Natha, Bhairava, Saiva, and Shakta traditions. By the eleventh century, these older traditions had begun to coalesce into the high forms of Hindu Tantra that were institutionalized as the elite Tantric traditions of Nepal: the Sri Vidya, Kali, Kubjika, Guhyesvari, Siddhi Lakshmi, and Taleju schools.” (p.1)

To my knowledge, King Hari Simha Deva introduced Taleju to the Kathmandu Valley in 1324 after he fled to the Valley from Simrongarh in India. We are also told that he belonged to the Karnataka Dynasty, and that is how the goddess Taleju made an entry to the Kathmandu Valley. There is no record of Taleju being a tutelary deity of Nepali kings prior to the 14th century. If there exists a written or oral record, then the readers should be informed. This is necessary to any historical revision.

Lidke alludes to the principle of Shakti throughout his book for the right reasons. The ample evidence he supplies, dating all the way from the time of King Manadeva of the Lichchhavi Dynasty to the last Shah Dynasty, ending in 2008, is commendable.

In his book Tantric Visions of the Divine Feminine: The Ten Mahavidyas, David Kinsley traces the history of Tripurasundari. According to Kinsley, before she was grouped among the ten Mahavidyas, Tripurasundari occupied a prominent position in both Kashmiri and South Indian Tantrism. This timeline is significant because of her 14th century connection with Taleju. Although Kinsley’s studies of Tripurasundari don’t specifically pertain to the Tripurasundari of the Kathmandu Valley, they are useful in understanding her story and connection to the Dasa Mahavidya cycle. Although Lidke mentions Kinsley’s work in his bibliography, he doesn’t cite Kinsley anywhere in his discussion of the goddess. Of course, he may have his own reasons for this.

I find it admirable that Lidke approaches the subject of Devi from multiple perspectives—oral, textual, and ethnographic. He interviews several living practitioners and scholars, and he quotes Sthaneshwar Timalsina throughout the book. It is apparent that Lidke has benefited from Timalsina’s knowledge, aiding in a complete digestion of the subject of tantra, and so producing a fine book. With the abundance of citations the author makes to his mentor, he may as well have dedicated the book to Timalsina.

Despite being deeply researched, The Goddess Within and Beyond the Three Cities is not without a few minor oversights. For example, on page 108, Lidke refers to the residence of Kumari as Indra Chowk, when in fact it is located near Durbar Square in Basantpur.

In comparing the beautiful goddess Tripurasundari with the three cities of Kathmandu, Patan, and Bhaktapur, Lidke would have done greater justice calling them by their ancient names, Kantipur, Lalitpur, and Bhaktapur, respectively. Since the word “pur” means “city,” using the ancient names of the Nepal Valley cities would have better fit the character of the Tripurasundari, who, indeed, is the “beautiful goddess of the three cities.” As an art historian, I would have also liked to see a full iconographical description of the goddess to situate her within the three temporal cities. The absence of a detailed description of her iconography, on which the book focuses, seems an oversight.

On page 19, Lidke says, “The Goddess, in her paradoxical nature as the unitary consciousness-power that embraces all opposites, is celebrated as both unmanifest (nirguna) and manifest (saguna), conscious (caitanya) and inert (jada), being and non-being (asat), transcendent (visvottirna) and immanent (visvamaya), absolute (paramartha) and relative (vyavaharika).”

Ontologically and epistemologically, what the author says makes sense; this is a scholar speaking from the point of view of Tantric texts. But how many members of the laity worshipping a deity in a goddess temple know the nirguna and saguna qualities of the goddess? Few to none, I would imagine. For an ordinary lay devotee, the saguna aspect of the goddess is the most important—it is what draws them to a temple to touch and view the image. Even in the Guheshvari temple, where there is no image of the goddess, devotees gather around the Kalasha (water jar) that covers the bubbling spring water from the ground—considered the embodiment of the goddess. This is enough for them to touch and feel her. The power she has in the form of holy water is what draws a believer, not the philosophical interpretations of scholars.

There are two sides of any religion— the philosophical and the ritualistic. Lidke’s book traces the deeply philosophical elements of Tantrism as manifested through the visualization of the goddess in the Kathmandu Valley. For the author’s perspectives on the goddess, I highly recommend The Goddess Within and Beyond the Three Cities to those seeking to understand the deeply philosophical nature of the goddess as it pertains to Tripurasundari of the three cities of the Kathmandu Valley.

Reviewed by Deepak Shimkhada, Claremont School of Theology, Claremont, California

_____________________

[1] Although the deposed Shah King still lives as a common citizen, the rule of Shah Kings as a dynasty ended when he was deposed by the people’s revolution in 2008.

Leave A Comment